Jeremy Heimans on New Power

David Colby Reed and Lee-Sean Huang interview Jeremy Heimans, CEO of Purpose and co-author of the book New Power: How Power Works in Our Hyperconnected World–and How to Make It Work for You.

Why do some leap ahead while others fall behind in our chaotic, connected age? In New Power, Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms confront the biggest stories of our time—the rise of mega-platforms like Facebook and Uber; the out-of-nowhere victories of Trump and Obama; the unexpected emergence of movements like #MeToo—and reveal what’s really behind them: the rise of “new power.”

Podcast Transcript

If you're shepherding a crowd rather than just a bunch of people on your payroll, what's different about that? And what's different in the context of a world in which there is a very, very big hunger to participate?

Lee-Sean: I'm Lee-Sean Huang, and you're listening to FoossaPod, a podcast about creativity, community, and the things that matter. In this episode, David Colby Reed and I talk about new power and how it's transforming business, social movements, and politics, with a very special guest.

Jeremy: Hey. I'm Jeremy Heimans, and I am the CEO of Purpose, which is a organization that works on movement building around the world, and helps other organizations who want to build movements. I am the coauthor of New Power.

Lee-Sean: First of all, what is power? Because a lot of people want power. We talk about power a lot. What is the difference between power, old and new?

Jeremy: We use Bertrand Russell's definition of power, which is the ability to produce intended effects. What we argue in the book, is that obviously for most of history, the dominant way that people have done this, is using what we call old power. Essentially, old power is power as currency. It's the kind of power that relies on what you have, what you know, what you own, that no one else does. It's that capacity to wield and spin down that power as currency that allows you to get what you want done. Now, what we've argued in the book, is that what we call new power is a form of power that does not rely on those dynamics. In fact, it's not the kind of power that you can hoard like a currency. It's the kind of power that works more like a current. It's something that surges with the participation of many, many people. It is often very difficult to control.

It often moves and changes as that current evolves. So you think of the #MeToo movement ... as it exercised an expression of new power. That movement doesn't have a leader at the top. It doesn't have an established hierarchy. It has many leaders. It has many forces that are converging, and it changes wherever it goes. In France, the #MeToo movement looks very different ("Denounce your pig" in French) to the #MeToo movement in the US, and the dynamics change.

And so the example we use in the very beginning of the book to contrast old and new power, is think of Harvey Weinstein as this kind of classic exemplar of frankly for decades what was a very successful execution of old power. The way he kept his position and was able to maintain the spread of abuse was because he understood the rules of old power. What we argue, is that the new power that helped to displace him is a very important force in the early 21st century. It hasn't displaced old power, but those two things are kind of battling and balancing in this era, which is why we wrote the book.

Old power versus new power

David: I'm really interested in this idea of new power as current. I'm curious, how much of that is dependent on our technological landscape? And I mean technology like writ large, not Facebook necessarily, but communication, social technology norms. You could call that like a techne around some of the elements of new power. But how much of that is unique to our current era?

Jeremy: Well, I think the question of what's unique is really interesting, because there's nothing new about social movements. There's nothing new about collectivism, collective commerce, any of these expressions of new power that we discuss in the book. What is new, is the speed, the scale, and the density of the networks that have emerged. That enables a whole new set of models that would not have been possible. So you think about Airbnb. 25 years ago, you could get a catalog in the mail every season, and that catalog would have apartments in it that you could swap with other people, right? It's not new, the idea of swapping apartments, but at the scale that a catalog could enable, there was no way you would transform the entire housing stock of cities in the way that Airbnb has done. Our argument is not that bottom-up dynamics are new or that networks are new. Of course they're not. But what is new, is the ability to do this at such a scale with such speed that entirely new things become possible, that would not have been possible 20 years ago.

Lee-Sean: So there was a phrase that I'd heard from your coauthor, Henry, in another interview, where he talks about new power as a way of scaling leadership, right? So if you think about movements like Black Lives Matter, they talk about being leaderful and using the technologies we have now, but also the social dynamics we have now to scale leaders, where you don't have to be sort of part of the executive team, there's things that you can do as an individual member of some movement to do something. Are there other examples of that kind of leaderfulness, or scaling leadership?

Jeremy: I think we're seeing it all the time in these new networks. So what people can now do...Think about the Women's Marches. We had some involvement with those. You remember when the Women's Marches began, someone emerged from nowhere, really, to put their name forward and say, "Let's do a Women's March." It wasn't an established organization. Once that happened, people all over the country just said, "Hey, I want to organize a Women's March in my town," and those people became leaders, de facto leaders, of their communities, rallying, in some cases, hundreds of thousands of people showed up to these individual Sister Marches in different cities around the world. So obviously, the technology allows you to do that, and not just do that in an atomized way, but do that in a way that it does connect you to a larger structure and movement. So we see this all the time.

You also see it with these business models like an Airbnb or a Wikipedia, where these kinds of super-participants emerge who effectively carry out key leadership functions, even though they're not on the payroll, or as you say, on the executive team. It's a different way to think about leadership. One benefit of the approach, is it insulates movements and organizations from being overly dependent on the fortunes of one individual.

So you think about something that Alicia Garza, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, told us that we write up in the book is when Medgar Evers and Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were killed, she said if you cut off the head of these movements, the body sometimes goes with it, dies. So that's not something you can do as easily in a movement in which there are many leaders.

She and her cofounders and some of the other leaders of that movement have thought very intentionally about how do you do that? How much does she move into the spotlight in order to corral attention for the movement, because people still expect leaders to act like leaders? One of the interesting dynamics she talks about, is how perhaps the most prominent individual to emerge out of the movement was ... or has been ... DeRay Mckesson. She points out that like, well, part of that is because people recognize a charismatic man as the form of a leader, and so the media kind of often flock to him and kind of want the movement to look like a conventional movement. But it's not. That's not the kind of movement that they're building. So it's a really interesting tension, I think.

That doesn't invalidate the role of individual kind of more directed leaders. Our argument in the book is not old power bad, new power good, or throw out the old power tool book, it's actually very much about how do you learn when to use old power, when to use new, how to combine them in order to get your intended effects? And that is a very subtle exercise, rather than one in which you throw out all structure and hierarchy.

David: I'm so glad that you hit on that point, because you and Henry take pains not to describe this in normative ways, but rather a positive kind of analysis, and a description of the world as we see it, or the world as it is, you know? In your interactions with folks when you're talking about new power either in a client service kind of context or a strategic advising kind of role, I feel like people tend to denigrate the familiar or the status quo ante in favor of the shiny new thing.

Jeremy: Sure.

David: And do you find that you've got to push back on that? How do these conversations when you're working on new power-style projects or bringing new power lenses to bear on problems, in concert with the other folks that are working on them, how does that play out?

Jeremy: That's a great question. I think we see both dynamics. One dynamic we see is, people whose lives and careers are built on old power ... And that is most people, particularly people over a certain age ... are very reluctant to have everything they know be invalidated. So you get resistance. What people actually want to hear, which is also the truth, which is what they've learned how to do is still very valuable.

Something we talk about in the book is that ... say, making a film. My dad spent most of his career as a documentary filmmaker. Back in the day, everything was kind of gated through government funding bodies back in Australia, right? So you would write a treatment, you would apply for funding, and the skills you needed to succeed in that world were, how do you navigate a really bureaucratic process? How do you know the right people? How do you establish credibility with a small number of elites, et cetera? Now, let's be honest, that's still a big part of how the world works, right? I say this to a bunch of people who went to Ivy League schools, those qualities and skills are still very, very valuable, right?

And yeah, it's also true that if you're making a film today, a whole other set of skills can get you a very long way. You can raise millions of dollars, if you're smart, in crowdfunding. Now, those people still tend to be the better connected people and the privileged people, but nonetheless, the skills involved in raising $5 million of funding at $50 a pop are very different to the skills involved in getting two $2.5 million checks. Part of that is about being better at storytelling, being better at building community. Those are a set of skills you need to do in order to rally large numbers of people in that way, being highly transparent, et cetera.

Those are two sets of skills. So in your question, yes, there are some people who just want to gravitate to the shiny new thing. There are some people who are clinging to what they know. I think in our work, our role is to try to balance those things, and to help people navigate a world in which these forces of old and new power are present and colliding. But most effectively, being blended in order to get stuff done.

Paradigm Shifts and Creating a Unified Framework

David: I'm curious, how did you come upon this framework of new power?

One of the examples I use in my teaching often, is Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, where he talks about this idea of you have a scientific paradigm, and it helps explain the information that we currently have. But over the course of its lifespan, there's information that accumulates that's like exogenous to the model. And like you just said, there's growing pile of facts and experience and experiments that don't really fit. Then he talks about, introduces, to the chagrin of everyone now, the term paradigm shift to talk about the ways in which a paradigm will shift in order to accommodate this corpus of stuff that's been external. Is that the process that characterizes your articulation of new power? Did you have examples from your business work or advocacy kinds of campaigns where there were just like these examples kind of accreting on the outside? Or how does that work, in your experience?

Jeremy: That's a really great question. I think we felt there'd be value and explanatory power in creating a unified framework, that identified the aspects of these new participatory dynamics that are found and are in common across business, politics, media, culture, et cetera. So that was our goal. We sort of felt like ... I obviously came from the political activism realm. Henry came more from the philanthropy realm. We'd both been doing a lot of work that you might call new power experiments. It felt to me that people needed a vocabulary and a lens in which to understand those things, and that the things that they had in common ... So for example, the dynamics that Airbnb were exploiting, people's hunger to connect in participate in new ways, people's desire to disintermediate big institutions like hotels, were not dissimilar to some of the dynamics that were fueling the growth of these new social movements in which people, again, wanted more to do than just give money or show up once in a while.

So these are the dynamics that informed my early career. I think about the organizations I was involved in starting, like GetUp! and Avaaz. These groups, political movements, were premised on the idea that people wanted to have more agency and act more directly in the social movements that they were part of. I think that's part of what led us to this description of these new power models, and these new power kind of values. It's obviously a framework that doesn't explain everything, but as we built it out, it felt like it explained quite a lot that was useful, which is why we kind of persisted with this work.

Jeremy Heimans, CEO of Purpose and co-author of New Power

Signal, Structure, and Shape

Lee-Sean: So you have several frameworks that you share in your book. I encourage people listening to check out the full book. But just as a preview, one of them is signal, structure, and shape, right? Could you explain how that framework works, and maybe take us through an example?

Jeremy: Yeah. We developed that framework as a way to understand what are the skills that a leader needs in a new power world. Part of what informed it was thinking, "Okay, so today, a lot of these new power leaders don't have a bunch of people on the payroll, where they have the ability to exercise a high degree of formal authority in a relatively controlled manner. So if you're shepherding a crowd rather than just a bunch of people on your payroll, what's different about that? And what's different in the context of a world in which there is a very, very big hunger to participate?

An example might be, of all people, the Pope, Pope Francis. Sure, he has some people on his payroll at the Vatican, but mostly he has a massive crowd of a billion plus Catholics. As we think about how he leads, he needs to do a bunch of things that are quite particular.

The first thing that he does, is he signals. The signaling work is really the work of a new power leader in sending the message to her or his crowd that their participation is valuable and needed. It's a signal to say, "I want you to step up and have agency." Now, that's also something that Donald Trump, unfortunately, did very well during his campaign. When he said things like, "If you punch a protester at my rallies, I'll pay your legal fees." When he retweeted his white supremacist supporters, that was also a very strong signal that he wanted to empower his crowd. So you can be a very good or a very nasty person doing this work.

Second skill is about structuring for participation. Beyond just sending the message that you want people to be more powerful, you also have to structure around that. There are lots of different ways to do that. You think about the Pope, and one of the things he did was ... he's attacked the power of the Vatican bank, which was holding a lot of power in the Catholic Church. He's tried to demote the Cardinals in favor of giving more decisions to the local priest. For example, they can now decide whether to marry a divorced person, whereas that used to be something that was held at the center. He's done a whole bunch of things that are structural. Not to say that that work is by any means complete.

The third skill is this idea of shaping. In a world in which you don't have formal authority, you have to be very good at shaping the norms of your crowd, if you're going to direct it in a way that makes sense. An example of a norm might be non-violence for the Black Lives Matter movement, and how those leaders enforce that norm, even though they're not sitting astride an organization that has a very clear organizational structure. So norms are important. The Pope's norm that he shaped is one of non-judgment. So you think about the way he's moved the church on homosexuality. The whole point of shaping is you're not changing the letter of the law. You're not changing doctrine ... And he hasn't on homosexuality ... but he has moved norms by saying, "Who am I to judge?" And that's a very unusual thing for a pope to say on that issue. The message he was sending in doing that was one of non-judgment, and encouraging other people throughout the Catholic Church hierarchy to adopt a less judgmental posture toward homosexuality.

None of this is to say the Pope is by any means all the way there on this stuff, but he's an interesting of a new power leader who's exercising these skills of signaling, structuring, and shaping.

Lee-Sean: So just to connect it to one of our previous episodes here on FoossaPod, our previous guest, Andrew Benedict-Nelson, actually talked about social norms a lot as well, in terms of if you want to do social innovation, it's not about the shiny gadget, it's not the next Twitter, but it's actually about identifying what the social norms are, and then trying to shift to those norms.

So in the case of the Catholic Church, if the norms were, "You can't get remarried if you're divorced," or, "You can't be gay and a good Catholic," as a new power leader, it seems like one of the ways to shift these norms is to either tolerate some sort of deviance, or in the case of Donald Trump's, it's actually about amplifying things that were maybe sort of unspeakable or not in the mainstream, and making them mainstream. Does that jive with your conception of how new power can shift norms?

Jeremy: Yeah. I think those are both examples. Trump has shifted norms precisely by speaking the unspeakable, and by legitimizing and surfacing those things. And so suddenly, he's been able to move the goalpost significantly on that. It hasn't largely been done on a policy basis on issues like race ... He's trying ... but a lot more of it is the shaping that he's doing, and the context that he's creating. So yeah, I think that's right. You can do it that way. I think you can also do it by highlighting aspects of your base and your crowd that have been invisible and silent.

New Power at Work

David: I want to shift gears slightly to talk about new power at work, because you and Henry write about different layers of control and interaction with platforms that are characterized by new power dynamics. At one point, you talk about like an algorithmic layer of organizational structure. So think about the algorithms that match drivers and passengers for your rideshare apps or whatever. You mentioned earlier one of the norms and behaviors around new power is the structuring for participation, and structuring for input. I think in those examples, you see these structures, especially at the algorithmic level of review, that are rules-based, that are not contingent necessarily, that have little recourse for appeal.

So I'm curious, obviously perfect examples don't exist in the wild, so there are degrees to which a model fits a reality, certainly. But how do you think about more of these automated or algorithmic control systems, especially when we're thinking about structuring interactions for participation, for that kind of expressive capability that you were describing earlier?

Lee-Sean: Or how is new power not holacracy?

Jeremy: Yeah, right. We point the ways in the book in which holacracy ... For those who are listening who don't know holacracy, it's a sort of trendy management philosophy that appears to be about obliterating hierarchy and creating self-managing teams. But really, it brings so much doctrinal process to the table that it ends up creating, I think, a lot more old power than traditional hierarchy does. Algorithmic management, as we call it in the book, is not necessarily going to lead to the kinds of human agency that it might be intended to do. In some cases, that kind of algorithmic management could actually be very coercive, or very much about surveillance. In other cases, it can be a very elegant way to establish trust or to solve structural problems in a network. So yes, the fact that an Uber driver or a Lyft driver can rate a passenger and that the passenger can rate her is valuable, in the way that that regulates trust efficiently.

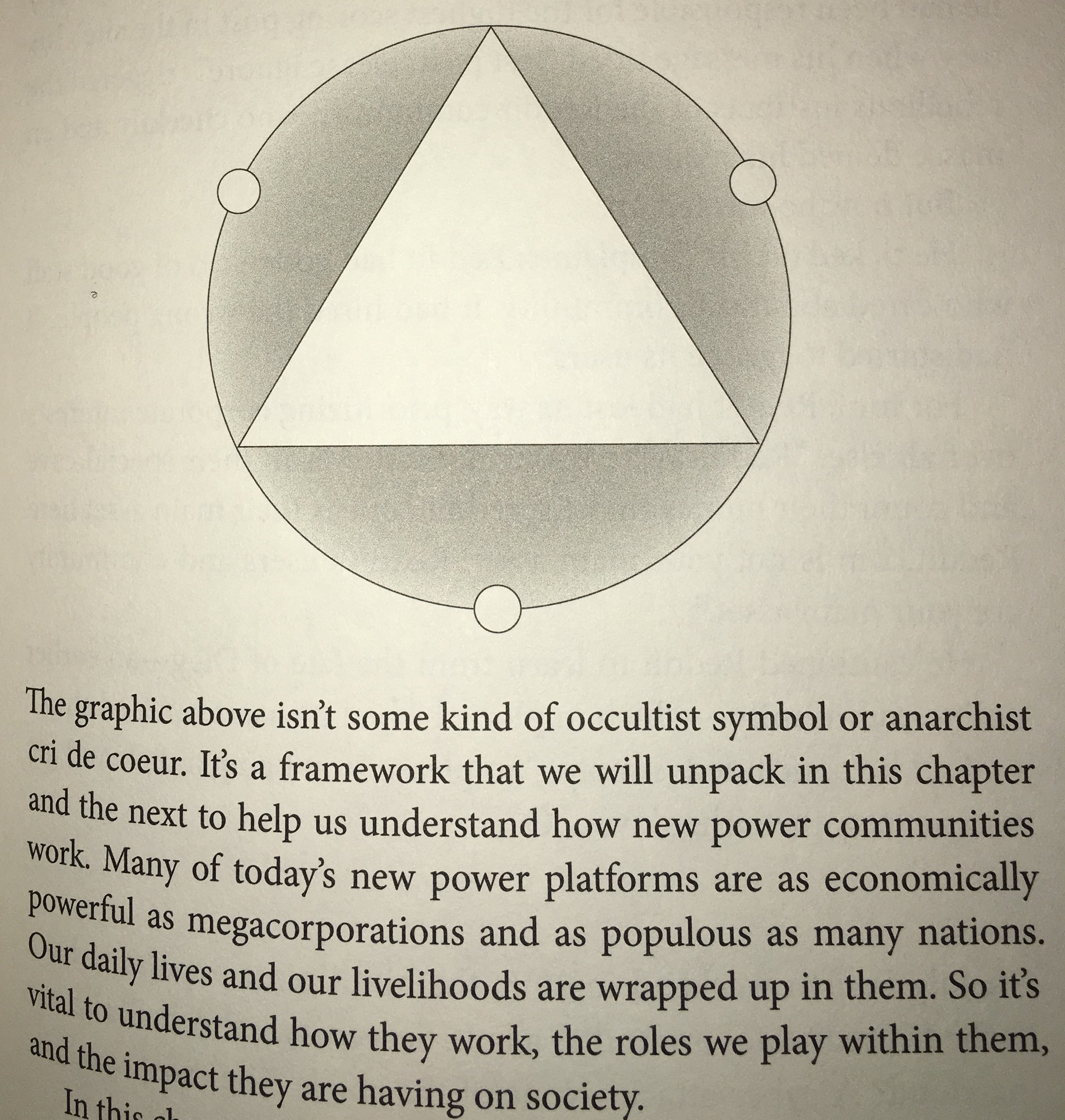

On the other hand, Uber preventing its drivers from seeing each other, talking to each other, engaging with each other because they're afraid that they're going to unionize, is also something that they're making an informed decision about using the product that is obviously leading to less people being empowered and connected. I think our argument in the book is that all of these things are ... that we have to apply a pretty stringent test and ask ourselves, "Which of these new power models are really creating more power for more people?" We have this framework in which we talk about a triangle and a circle. The triangle is the network. The super-participants, which in, say, Lyft's case are its drivers, the participants, it's riders, and the platform.

But around that triangle is a circle. That circle contains all of the actors that are impacted by these networks. In a world in which you've got networks like Facebook that are arguably more powerful than states, that becomes very, very important. So dotted around that circle, you've got the people who aren't users of those platforms. How are they impacted? You think about Airbnb and the externalities that come from what happens inside that network for people who might have their own homes and subject to increased rent or other dynamics. You've got governments. You've got media. You've got competitors. So thinking smartly about how each of these algorithmic decisions impact not just the triangle, but also the circle, and the extent to which you can create a harmonious triangle and circle, which is difficult, right? It's hard to get harmony even within the triangle, let alone when you introduce the circle. So that's one of the things that we talk about.

The triangle and the circle from chapter 5 of New Power

Lee-Sean: So for the Harry Potter fans out there, it looks like the Deathly Hallows for participation.

David: We can provide an image on our website. I think this is a really interesting point, about identifying the stuff that fits in the circle. I mean, again, the triangle is the network, and the circle includes the expanded set of stakeholders or channels. We are all stakeholders in environmental sustainability, even if we are not narrow stakeholders in the sense of being shareholders or employees or impacted by in a particular community.

Jeremy: That's right.

David: How do you go about identifying the kinds of stakeholders and other channels that fit in that circle? This is one of the things that we do just in our workshops, so community-centered design practice. It's like, try to identify the expanded set of stakeholders. I'm really curious to hear about how other folks think about this. And the kinds of conversations that you have with teams or clients or whatever when you're trying to expand that group, you know?

Jeremy: Yes, it's a great question. Well, I mean, I think one of our arguments in the book is that these new power models, because they can scale and command participation so effectively, start to have massively complex circles around them. So you think about the unintended consequences of Mark Zuckerberg's creation, and you think about how massively it's impacted elections and public discourse and extremism, et cetera. I think a lot of these networks start to become very significant. You then think, okay, from the perspective of public interest, that's what leads you to thinking around, "Can we apply, should we be applying our public interest test to something as important as this?" Because what's complex about these platforms, is they start in this kind of benign way, someone in their garage, they're in the realm of commerce, they're exciting, they're often very addictive.

So going from that to, "Wait, this thing is a public good, effectively." Now that they've got as much scale as they've got in it, it becomes a public good, becomes something that is a necessary provision for everybody. But it's not a public good, because it's privately owned, and it's controlled by a small number of people. So this is the tension, I think, as these new power models emerge. If you could see the end, you can see how big they can get, you'll probably approach it very differently to the way you would approach them in their infancy. I think we're dealing with the consequences of that right now.

David: I mean, that's just this fascinating idea, that stuff that is characterized by new power models, if the new power model is held through, they grow to become quasi-public good kinds of institutions or services or products and so on. Apart from the Facebook example, can you give some other examples of things that are teetering on that border of public good, or have the potential to? I'm curious where you see some of them.

Jeremy: Well, yeah. I think a lot of these, you could see how many industries could end up being transformed. You think of the real estate industry. You think about the impact that WeWork and others are having on the office space. Right now, I was talking to a friend who runs one of these big players. He was telling me that right now, WeWork is a small fraction of the total office space in the world, but the trajectory is such that in 30 years, a few of these companies are basically going to have swept up the vast majority of inventory. So you then think about the implications of that kind of market power, and you think about how different that is from these very fragmented models. And then you think, "Well, what happens when those companies get into a dispute with regulators, given how much market power they've got?" So you think about that. You think about transport. If Uber takes over transportation infrastructure, again, they've got enormous sway on something that has big implications for society as a whole. So it's all around us, I think, these dynamics.

David: I'm fascinated by the idea of WeWork needing to think about the implications of its business model for the ways in which people work. There are implied responsibilities in that direction that I don't ... I mean, I don't know the WeWork or any other example particularly well there ... but I suspect that there aren't too many people having these discussions about what the obligations are in this quasi-public good kind of way of arranging for sustainable work arrangements with people. It makes me think about antitrust too, because this is one of the things that's implied in your analysis here, that when we think about antitrust ... What's left of antitrust ... we think about it in terms of consumer welfare and, you know, does it lower prices? Sounds like there are other dimensions to thinking about public good and antitrust that are especially salient in new power models. I don't know if we have much vocabulary to speak about it.

Jeremy: I think at the moment, I think regulators are unlikely to be sophisticated enough to balance benefits to users, you know, so the framework to think about market power may not be adequate for the complex implications of these platforms. Because part of the benefit of the platforms are the network effects. You know, that's why in the book we talk about the framework in which these platforms operate. So we say interoperability, the ability for you to take your data in and out in a suitcase effectively in and out of the platforms, the ability to make it really seamless to move your content around becomes critical. In some ways, that's more important than whether you break up Facebook into five pieces or two. What's actually more important, is the interoperability.

So I think the balance for regulators is going to be, "Don't squash the benefits to users." What you don't want, is a world in which there's less interaction and connectivity because of the risks and negative consequences of these platforms. We want as much of the agency and connectivity, with fewer of the dangers. That's not an easy thing. I don't really trust traditionally minded regulators to get that right, but we'll see how it goes.

Book Recommendations and Doing More with New Power

David: Do you have any recommendations for books or other things that you're reading, that you think are related to either this theme or some other part of your life or work that you want people to know about?

Jeremy: Two books that I'm engaging with at the moment are Johann Hari, my friend's book on depression and social isolation, which is called Lost Connections, and a book about trust by my friend, Rachel Botsman, called Who Can You Trust?, which is about many of these questions around how norms and the construction of trust has been changed by these sort of algorithmic platforms.

Lee-Sean: Besides reading the book, obviously, what are some things that folks listening to this, whether they're business leaders or folks doing activism out in the world, what can they do to start incorporating new power as part of their practice?

Jeremy: Well, yeah, I think a lot of it is about structuring experiments, which we talk about a lot in the book. You've got to be prepared for some things to go wrong.

We tell the story in the book of Boaty McBoatface, which was an established research institution in Britain who'd built a very expensive research vessel, and they asked the crowd to name the ship, and the crowd said, "Sure. Let's call it Boaty McBoatface," and they said, "Hmm, I don't think we can do that." Part of the work is becoming familiar with these new repertoires. What does it look like to use new power alongside old power? How do you when to use which? That's often where the work really comes together. But I'm going to say it's as much about methods as it is about a mindset. That's why we sort of start the book by grounding people in a way of thinking, rather than just in a set of tools. And then we share with people those tools in a whole bunch of different areas.

You guys have been a great and wonderful support for the work and for the book, and have built on it and added to it. No podcast would be complete without a plug for WeWashing, which I think was the only exogenous idea, the only idea that we didn't coin in the new power glossary, which is now being shared around the world, including with the entire staff of the World Economic Forum the other day by Professor Schwab.

David: Well, I mean, Lee-Sean, you know how to coin a phrase. Thank you for that. Thank you for your time in helping us think through some of these questions about new power in terms of social movements and business models. I guess I'd love to end on the question of, what next? What are you working on in the new power space? What has you most excited, in terms of projects or campaigns or stuff exogenous to Purpose?

Jeremy: Well, I think the work on new power is going to be ... all these people have now been exposed to this thinking. It wouldn't be new power if we then just kept building upon it from the top. So the answer is going to be, can we create a generation of people who start practicing and using these new power skills, and who start training each other in those ideas and building upon them? So I think my dream would be in five years' time, there are tens of thousands of people around the world who have essentially become these new power trainers, who are helping spread this lens, this mindset, in organizations that matter, that are doing good and important work in the world.

And in parallel, that work is being built on and adapted and made extensible in many, many, many sectors and geographies in which the original framework we set out ... To come back to your point about paradigm shifts ... was insufficient. And the pile of things outside the paradigm starts to mount. We have to see some adaption of the work that comes from how it lives in practice.

Lee-Sean: Jeremy Heimans, thank you so much for coming on FoossaPod today.

David: It's been a really helpful way of thinking about our work, categorizing some of the things that we're seeing, and just want to say thank you for that.

Jeremy: Thank you, Lee-Sean, and thank you, David.

Lee-Sean: That's all for this episode of FoossaPod, a podcast about creativity, community, and the things that matter. FoossaPod is a production of Foossa, a creative consultancy that works for and with communities to tell stories, design services, and build new forms of shared value.

Please subscribe and leave us a review on Apple Podcasts, or visit us on our website, foossa.com/podcast, where you can also find a link to buy a copy of the book New Power by our guest, Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms.

Music this episode by Justin Mahar.

I am Lee-Sean Huang, until next time.